|

Mutiny on the Bounty Fletcher Christain led a mutiny aboard H.M.S. Bounty April 28, 1789

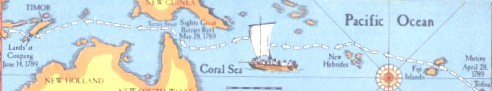

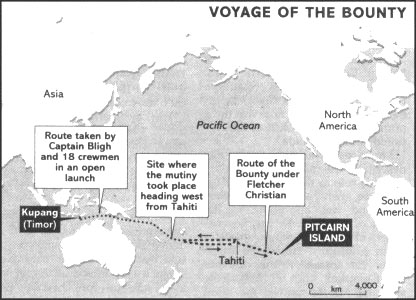

"A voyage of the most extraordinary nature that ever happened in the world," the exhausted British naval commander wrote in his last entry in his log, "let it be taken in its extent, duration and so much want of the necessaries of life." William Bigh, 35, was hardly exaggerating. On April 28, according to Bligh, he was assaulted and seized by armed mutineers aboard his own ship, the H.M.S. Bounty. The mutineers forced the captain and 18 loyal crewmen into a longboat, but in 43 days of wandering, Bligh managed to guide the 23-foot craft over some 3,600 miles of stormy and little-known seas to a safe harbor in Coupang (Kupang) on the remote Dutch-ruled island of Timor. Several of the ragged crewmen were gaunt and sickly (their daily rations: 1˝ ounces of bread and 1 gill of water), but only one had been lost (stoned to death by natives). The insurrection broke out in the midst of what Bligh had considered a peaceful voyage in search of breadfruit. Bligh himself was the first Englishman to discover the usefulness of this exotic plant as a food -- he was even nicknamed "Breadfruit Bligh" -- when he took part in Captain Cook's third voyage to the Pacific (1776-1780). Commissioned to bring breadfruit trees to the West Indies to help feed the African slaves there, Bligh cruised for some months around Tahiti (Otaheite, pronounced Ta-hee-tee) and loaded the Bounty with 1,015 of the trees. But while his crewmen were searching the islands, they often succumbed to various temptations. Says Bligh: "The women are handsome -- mild in their manners and conversation -- possessed of great sensibility..." Seven times during the voyage, Bligh had to resort to floggings to restore discipline. The Bounty, (originally the Bethia) had been purchased by the Navy and taken to Deptford for refitting and supply on May 26, 1787. It carried four 4-pounders and ten swivels. A refit commenced in June with the great cabin converted to house pots for holding breadfruit plants and gratings fitted to the upper deck. Captain William Bligh was appointed master on August 16, 1787. On December 23, 1787, the Bounty sailed from Spithead on its ill-fated voyage to Tahiti. The ship was too small and cramped -- displacing 215 tons with on deck dimensions of: Length 90 feet 10 inches; breadth 24 feet 3 inches -- for such a long mission. A more common size for ships making such a journey would have been 300-450 tons. On the afternoon of April 27 the captain noted the disappearance of a number of coconuts that had been stored between the ship's guns. He questioned the officers about how many coconuts they had acquired for themselves. One of them, Chief Mate Fletcher Christian, answered angrily: "I do not know, sir, but I hope you don't think me so mean as to be guilty of stealing yours?" Bligh answered just as angrily: "Yes, you damn'd hound, I do. God damn you, you scoundrels, you are all thieves alike, but I'll sweat you for it, you rascals." The next morning, just before sunrise, Christian and six accomplices struck back. Said Bligh in his report: "They came into my cabin while I was fast asleep and seizing me, holding naked bayonets to my heart, tyed my hands with a cord behind my back and threatened instant death if I made the least noise." Despite the warning, Bligh cried out for help, in vain. "I was hauled out of bed," he continued, "and I was forced on deck in my shirt with my hands tyed behind my back in so severe a manner that I suffered the severest torture." Bligh's report continued that he "degraded Christian for his villainy" and demanded to know "the cause of such a violent act," but Christian answered, "Not a word, sir, or you are dead this instant."

The 25 assembled mutineers kept shouting threats of death -- "Damn his eyes! Blow his brains out!" -- but their actual plan was to set Bligh adrift in the ship's leaky cutter, a "rotten carcass of a boat." When several crewmen wanted to go with him, however, the mutineers agreed to let them use the more seaworthy longboat and to take some supplies: a 28-gallon cask of water, 150 pounds of bread, 25 chunks of pork, 6 quarts of rum, four sabres, a tool chest and a compass. Even at the last minute, Bligh argued with the mutineers: "I'll pawn my honor, I'll give my bond, Mr. Christian, never to think of this if you'll desist." Said Christian: "No, Captain Bligh, if you had any honor, things had not come to this." The mutineers then cut the longboat loose and sailed eastward, shouting, "Huzza for Otaheite!" Since Bligh's boat was loaded to within 7 inches of the gunwales, he first decided to sail to the nearby island of Tofoa, where the natives had previously been friendly. Now that Bligh no longer commanded the Bounty, however, some 200 natives surrounded his foraging party, killed one seaman and chased the others out to sea. ("In the course of this," Bligh wrote in his log, "I saw five of the natives about the poor man they had killed, struggling who should get his trousers, and two of them were beating him on the head with stones.") The result of that attack, according to Bligh, was that "I was earnestly sollicited by all hands to take them toward home ... I therefore bore away across a sea, where the navigation is dangerous and but little known and in a small boat deep loaded with 18 souls, without a single map and nothing but my own recollection and general knowledge."

Soon it began to rain, and the swelling seas broke over the little boat's stern. Bligh ordered that all spare sails, rope and clothing be thrown overboard, and the bread was stored in the tool chest in an attempt to save it from rotting. Everyone had to bail constantly. Bligh's log: "A situation equally horrible perhaps was never experienced." Despite his precautions, the storm rotted the bread, but the castaways had to eat it anyway. Said Bligh: "Our wants are now beginning to have a dreadful aspect." After a little more than a week at sea, the boat passed through the northern edges of the Fiji Islands, but there was no chance of rescue. Bligh's log: "I dare not land for fear of the natives, having no arms." At one point, two Fijian canoes suddenly appeared and began chasing Bligh's longboat, so the Britons "rowed with some anxiety" until the Fijians gave up the pursuit. To the west of them lay another 720 miles of open sea, with no land until the New Hebrides. The storms began again. Bligh's log: "A prodigious fall of rain, with severe thunder and lightning ... At length the day came and showed to me a miserable set of beings, full of wants, without anything to relieve them." Bligh doled out rum, one spoonful per man. He steered north of the New Hebrides and on into the Coral Sea, more than 1,725 miles across. And again: "The night was truly horrible, and not a star to be seen ... Constant rain, at times a deluge ... At dawn some of my people seemed half dead, and I could look no way but I caught the eye of someone in distress." It was on May 25, after almost a month at sea, that one of the famished crewmen managed to seize a noddy, a tern about the size of a pigeon, in his bare hand. Bligh divided the tiny bird into 18 pieces, and it was "eat up, bones and all, with salt water for sauce." The presence of the bird heralded land. After three days, the castaways finally heard the thunderous beating of breakers on the Great Barrier Reef, and once Bligh had steered them to the shallows inside the reef, they "returned God thanks for his gracious protection." They now could find food -- they scraped oysters from the reef and carved out the pulp of palm trees -- but they still were not out of danger. On one occasion, when they encountered a band of armed natives -- "They appeared to be jet black with short bushy hair and quite naked" -- they fled to deep water again. They navigated through the Torres Strait and toward Timor, still some 1,080 miles to the west. And the rains swept down again. Bligh's log: "People began to appear very much on the decline ... An extreme weakness, swell'd legs, hollow and ghastly countenances, great propensity to sleep, and an apparent debility of understanding, give me melancholy proofs of an approaching dissolution of some of my people, if I cannot get to land in the course of a few days." But at dawn of June 14, he did reach his goal on the coast of Timor. "It is not possible," he observed, "for me to describe the joy that the blessing of seeing the land diffused among us." Now that Bligh had achieved the feat of bringing his men to safety, his next goal was revenge. In Timor, he bought a 34-foot schooner and renamed it the H.M.S. Resource. He sailed the craft back to England where he attempted to convince a court-martial to name the 25 mutineers as pirates, and to condemn them to hanging should they ever be caught. The Mutineers Seek a HavenAfter the mutineers set Bligh and 18 crewmen adrift in the ships launch Chief Mate Fletcher Christain then safely sailed the pirated and under-manned Bounty on an epic 8,000 mile Pacific voyage in search of a haven. He first sailed back to Tahiti, then with six Tahitian men and twelve women aboard, they eventually came upon Pitcairn Island where they settled in 1790. Some mutineers had elected to stay at Tahiti where they were captured and sent back to England, on board H.M.S. Pandora, and were court-martialed.

Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island was descovered by the son of Major Pitcairn, seaman on board H.M.S. Swallow. It is a small volcanic Island situated 1,450 miles east-south-east of Tahiti, and 3,540 miles east-north-east of Auckland New Zealand. It is a rugged island of formidable cliffs, giving no easy access to the sea even at Bounty Bay, the only harbor. Access to the sea is difficult. Temperatures range from 19 to 24 Degrees Celcius and the average annual rainfall is 80 inches. Early Pitcairn history is not known but archaeological remains suggest it was inhabited by Polynesians about six hundred years ago. Settling on Pitcairn in 1790, the Bounty was scuttled and burned to sea level, so as not to be seen by passing ships. Although it is an island paradise, the mutineers and Tahitians brought jealousy, violence and blood shed. By 1800 the only male survivor was John Adams who led the community by introducing education and religion until his death in 1829. It was not until the Topaz, under the command of Capt. Mayhew Folger, visited Pitcairn Island in 1808, that the story of the Pitcairn settlement became known. Folger, on his return to the U.S., informed the British but they were occupied with concerns in Europe and did nothing until 1814 when H.M.S. Briton and H.M.S. Tagus called at the Island.

By then the population had reached 40 and by 1831 had increased to 86 of whom 79 were born on the island. Concerns that the community was out-growing the small Island, led to the evacuation to Tahiti in 1831, but within six months the Islanders had returned to Pitcairn. In 1856 the population had reached 193, and the islanders again abandoned Pitcairn to commence a new life on Norfolk Island, which the British Government had made available to them. However, 43 Pitcairners found their way back to Pitcairn Island and, since then, the island has been permanently occupied with the population peaking at 233 in 1937. In recent years, there has been a steady emigration to New Zealand and on 31st December 1992 the resident population was 54. Pitcairn is a British settlement under the responsibility of the British High Commissioner in New Zealand. Pitcairn Island A paradise Pitcairn could have been, for the mutineers this was not to be. Fletcher Christain, John Williams, Isaac Martin, John Mills and William Brown were murdered by the Tahitians. Mathew Quintal was killed by Young and Adams in self defence. William McCoy became insane and jumped over a cliff. Edward Young died of asthma. John Adams was the sole survivor and died in 1829. The Pitcairn Community became too large for the small island to support and, in 1856, many descendants moved to Norfolk Island Table of Events 1767 Pitcairn Island was discovered. 1774 Norfolk Island was discovered by Captain James Cook on 10 October. 1789 The mutiny aboard H.M.S. Bounty on 28 April. 1790 Nine mutineers, eighteen Tahitians and one infant landed on Pitcairn Island. 1808 The Pitcairners were discovered when the American ship Topaz called at the island. 1831 The Pitcairn population moved to Tahiti but returned to Pitcairn within six months. 1838 Captain Elliott of H.M.S. Fly on behalf of the British Crown, took formal possession of Pitcairn Island. 1853 The Pitcairn Islanders requested the British Government to move them to Norfolk Island. 1856 The Pitcairn Islanders embarked on the Morayshire on 3 May -- they landed on Norfolk Island on 8 June. 1859 A grant of twenty hectares (nearly 50 acres) of land was made to the head of each family on Norfolk Island. Court-Martial results of crew members captured on Tahiti -- The Court

Norfolk Island Norfolk Island is a paradise in the South Pacific with a wealth of beauty and charm. Norfolk lies in the Pacific Ocean 1200 miles from Sydney Australia and 700 miles from Auckland New Zealand, discovered by Captain James Cook on his second world voyage in 1774. Cook reported that the island was fertile and uninhabited. He is believed to have landed at Duncombe Bay, and a memorial was erected there in 1953. When the British Government was preparing to establish a convict settlement in New South Wales, Captain Arthur Philip, who had been appointed first Governor, was ordered to secure the island for the crown at the earliest opportunity. Accordingly, on February 14, 1788, shortly after the founding of Sydney, Phillip sent Lieutenant P.G. King to Norfolk Island in H.M.S. Supply with a small party, which included nine male and six female convicts, in order to take possession of the island and to establish a settlement. After five days' search for a suitable landing place, King disembarked his small party on March 6 at the head of Sydney Bay, on the southern side of the island. This settlement, Kingston, thus became the second British settlement in the Pacific. The work of clearing land to form the settlement was arduous, as the whole island was covered with the famous Norfolk Island pines. Free settlers and convicts continued to arrive, until the population grew to about 1,000. But the settlement was expensive to maintain, and the lack of a harbor, which led to the loss of H.M.S Sirius in 1790, made communication difficult. In 1803, the Secretary of State for Colonies ordered the removal of the inhabitants to other settlements at Port Phillip or Van Diemen's Land. Captain Philip King, then Governor, who entertained great hopes for Norfolk Island, did not pursue these instructions with any vigour. However, removals were made during Bligh's governorship. Governor Macquarie completed the transfer in 1813, when the last convicts were removed to New Norfolk in Van Diemen's Land. In 1826 the re-occupation of Norfolk Island began and another convict settlement established. The fertile lands were tilled again; a program of bridge building and other public works was pushed ahead. Most of the substantial buildings and stone ruins on the island today date from this period. So also does its unsavoury reputation as a ghoulish place. Partly due to protests over the brutality of the convict system, Norfolf was once more scheduled for abandonment. After this decision had been made, it was suggested that the island should become the new home of the Pitcairners, and the evacuation was arranged to coincide with this plan. By May, 1855, only a storekeeper and twelve men were left to await the arrival of the new settlers. The following year the first free settlement was established by Pitcairners. Since then there has been a continuous history of free settlement and a public holiday known as Bounty Day now celebrates the first settlement of 1856. The descendants of the Bounty mutineers today forms the nucleus of the Norfolk Island community. |

All rights reserved. For details and contact information: See License Agreement, Copyright Notice. |