|

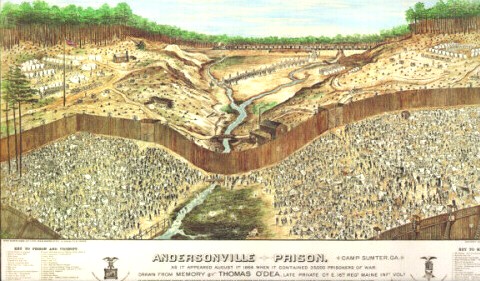

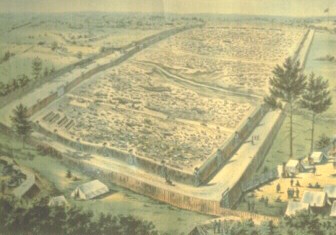

Andersonville Prison A Confederate Death Camp Opened: February, 1864 In November of 1863, Confederate Captain W. Sidney Winder was sent to the village of Andersonville in Sumter County, Georgia, to assess the potential of building a prison for captured Union soldiers. The deep south location, the availability of fresh water, and its proximity to the Southwestern Railroad, made Andersonville a favorable prison location. In addition, Andersonville had a population of less than 20 persons, and was, therefore, politically unable to resist the building of such an unpopular facility. So Andersonville was chosen as the site for a prison that would later become infamous in the North for the thousands of prisoners that would die there before the war ended. After the prison site was selected, Captain Richard B. Winder was sent to Andersonville to construct a prison. Arriving in late December of 1863, Captain Winder adopted a prison design that encompassed roughly 16.5 acres which he felt was large enough to hold 10,000 prisoners. The prison was to be rectangular in shape with a small creek flowing roughly through the center of the compound. The prison was given the name Camp Sumter.

Beginning in January 1864, slaves from local farms were used to fell trees and dig ditches for the stockade. The enclosure was approximately 1010 feet long and 780 feet wide. The walls were pine logs cut on site and set vertically in trenchs about 5 feet deep. The poles were hewn square, 8 to 12 inches thick, and "matched so well on the inner line of the palisades as to give no glimpse of the outer world" (Hamlin 1866: 48-49). A light inside fence, known as the 'deadline,' was erected about 19-25 feet from the outer barrier to mark off a 'no-man's land' to keep prisoners from the stockade wall. A prisoner crossing this line would be immediately shot by sentries posted at intervals around the wall. Included in the construction of the stockade were two gates positioned along the west stockade line. The gates are described in historic accounts as "small stockade pens, about 30 feet square, built of massive timbers, with heavy doors, opening into the prison on one side and the outside on the other" (Bearss 1970: 25). Each gate contained wickets (door-sized entry-ways).

Prisoners began arriving at the prison in late February 1864 and by early June the prison population had climbed to 20,000. Consequently, it was decided that a larger prison was necessary, and by mid-June work was begun to enlarge the prison. The prison's walls were extended 610 feet to the north, encompassing an area of roughly 10 acres, bringing the total prison area to 26.5 acres. The extension was built in about 14 days by a crew of Union prisoners consisting of 100 whites and 30 African Americans. On July 1, the extension was opened to the prisoners who subsequently tore down the original north wall, then used the timbers for fuel and building materials. By August, over 33,000 Union prisoners were held on 26.5 acres. Due to the threat of Union raids (Sherman's troops were marching on Atlanta), General Winder ordered the building of defensive earthworks and a middle and outer stockade around the prison. Construction began July 20th and consisted of Star Fort located southwest of the prison, a redoubt located northwest of the north gate, and six redans. The middle and outer stockades were hastily constructed of unhewn pine logs set vertically in wall trenches about 4 feet deep. The middle stockade posts projected roughly 12 feet above the ground surface and encircled the inner prison stockade as well as the corner redans. The outer stockade, which was never completed, was meant to encompass the entire complex of earthworks and stockades. The posts of the outer stockade extended about 5 feet above the ground surface. By early September, Sherman's troops had occupied Atlanta and the threat of Union raids on Andersonville prompted the transfer of most of the Union prisoners to other camps in Georgia and South Carolina. By mid-November, all but about 1500 prisoners had been shipped out of Andersonville, and only a few guards remained to police them. Transfers to Andersonville in late December increased the numbers of prisoners once again, but even then the prison population totalled only about 5000. The number of prisoners would remain this low until the war ended April 9, 1865. During the 15 months that Andersonville operated, almost 13,000 Union prisoners died of malnutrition, exposure, and disease; Andersonville became synonymous with the atrocities which both North and South soldiers experienced as prisoners of war. After the war ended, the plot of ground near the prison where nearly 13,000 Union soldiers had been buried was administered by the United States government as a National Cemetery. The prison reverted to private hands and was planted in cotton and other crops until the land was acquired by the Grand Army of the Republic of George in 1891. During their administration, stone monuments were constructed to mark various portions of the prison including the four corners of the inner stockade and the North and South Gates.

See also: W. Tennessee Unionist in Andersonville Sinking of the Sultana |

All rights reserved. For details and contact information: See License Agreement, Copyright Notice. |